New MH370 Evidence from the Sea [S2Ep38 video]

Ten years after the first debris came ashore, new data provides a new understanding

This week is the 10 year anniversary of the discovery of the first piece of physical evidence in the case of the missing Malaysian Airliner, MH370. When the badly damaged right flaperon washed ashore on La Réunion, a French island in the western Indian Ocean, on July 17, 2015, it immediately caused a worldwide sensation. Scientists realized that the barnacles found growing on the flaperon could provide important clues as to where it had drifted from — and that, presumably, would at last reveal the plane’s crash site. At a time when the seabed search had proven frustratingly empty, they hoped that this information could be the key to finally solving the case.

But scientists were missing an important piece of context: a robust understanding of how exactly Lepas anatifera barnacles grow when floating in the open ocean. In the years since, that understanding has proven elusive. However, using data from the Atlantic Oceonographic & Meteorological Laboratory in Miami and the assistance of volunteers living by the ocean’s edge, I’ve finally been able to collect specimens of known age that put the growth of the flaperon barnacles in context and reveal when the object went into the water. It turns out that scientists’ initial expectations were way off the mark.

I’m going to tell you all about it, but first let me set the stage with a little background info on these creatures. Goose barnacles of the species Lepas anatifera grow all over the world in temperate and tropical oceans. In their larval phase they disperse all throughout the ocean, looking for something to attach to, so that if you throw any floating object into the ocean, anywhere in the world, within a week you will start to have little tiny Lepas growing on it.

This is a pain in the butt if you own a boat, but it’s great if you’re trying to figure out how long something has been in the ocean, because anything that goes in the ocean is basically getting a natural data logger attached to it.

We talked a lot about this in Season 1, but suffice to say that scientist have used Lepas to estimate how long things like ghost fishing nets, tortoises and even dead bodies have been in the ocean. By combining that estimate with reverse-drift modelling you can figure out where the things started their journey through the ocean.

Here’s the thing, though. You can use the size of the barnacles to estimate how long something has been in the water only if you know how fast those barnacles grew.

And back in 2015, we didn’t really have very much good data on how barnacles grow.

But because the mystery was famous it spurred a whole bunch of research into the question. And once the data started coming in, scientists realized that some of the assumptions that had been made at the time turned out to be wrong.

For instance, researchers had assumed that Lepas grow in the same way all over the world. Turns out they don’t. Researchers who looked at barnacles growing the cold water currents off the coast of South America found they grew only to 20 mm, which is much smaller than the barnacles on the flaperon. Meanwhile, researchers in southeastern Australia found that they could get as big as 45 in just 30 days. That’s much bigger than the flaperon barnacles.

What that tells us is that if we want to use the flaperon’s barnacles to tell us how long the thing was in the water, we have to know more about how barnacles grow in that particular part of the ocean, namely the tropical western Indian Ocean.

And over the years some really intriguing work has been done. In one study, researchers in Tanzania found a tortoise that had washed ashore covered in Lepas, and they used that to figure out where it had drifted from, because tortoises are terrestrial animals that don’t live in the ocean, so it must have fallen in or been thrown in.

The barnacle shells were 20 mm long. In their study the researchers referred to earlier findings involving fish accumulation devices, or FADs, that found that after 11 weeks in the water, these devices had barnacles that are 30 mm long. So they figured that meant the tortoise had been adrift for 6 or 7 weeks.

OK, but the barnacles on the flaperon are bigger than this. How much bigger? Well, I recently gained some significant new insight into this.

When the Malaysians released their final report in 2018 they included as an annex a paper by a French marine biologist who studied the barnacles. It revealed that the largest specimen measured 36 mm. We also knew that the French had loaned out some other specimens to other scientists that were significantly smaller, around 25 mm. At the time it really wasn’t clear why they ones they leant were small, because smaller means younger, which means they wouldn’t provide evidence about the flaperon’s full journey.

For many years the French were very secretive about what they had. But gradually they grew more open, and shared more information, and one of the people they shared pictures of their samples with shared them with me. It turns out that while the biggest is 36 mm long (as we already knew), there are only a handful of others that are bigger than 30 mm. The vast majority are between 20 and 30 mm or even smaller.

In seems that the reason the French didn’t share many big barnacle shells is simply that there were so few of them.

Back in Season 1, episode 24, I interview Dr Martin Stelfox, who had conducted an experiment where he let Lepas grown on buoys in the Maldives. He wanted to understand how barnacles grew in that part of the ocean so he could figure out where ghost fishing nets were coming from.

His experiment was unique because his team was able to observe individual barnacles as they grew, and so really understand how they changed over time.

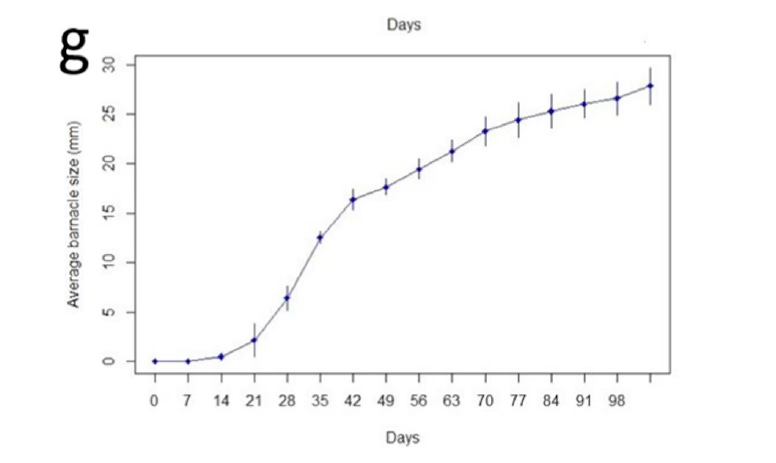

The paper that they published showed that they had a growth curve that looked like this:

Now this chart doesn’t show the biggest barnacles, it shows the average size. So after 105 days, or three and a half months, the average size was 27.9 mm and the biggest was 35 mm.

And well, that’s about what we see with the flaperon. So based on Stelfox’s data, you might think that the flaperon had been in the water about 105 days, or three and a half months.

But here’s a question: do barnacles grow the same on floating objects the same way they do on fixed buoys? It’s a reasonable assumption, but it might not be right.

After all, water should flow more past a fixed mooring, versus on a buoy that’s floating with the current. And since Lepas feed by plucking food from the water as it flows past, you might expect them to eat more and grow faster on a fixed mooring.

To really understand how the flaperon barnacles grew, we’d ideally have a reference population that’s been floating freely through the ocean. But how are you going to do that? How are you going to study something that’s way out in the middle of the ocean and moving randomly?

Well, on the 10th anniversary of MH370’s disappearance I did an episode where I did a photogrammetric analysis of barnacles that were found growing on a capsized boat that had drifted from Australia to the French island of Mayotte, near Madagascar, over the course of 8 months. Now I only had usable imagery of a very small sample, but it seemed that the largest of them were about 40 mm. That seemed to me to fit with Stelfox’s data and suggested that Lepas will get bigger than they were on the flaperon, and that the flaperon had spent less than eight months in the water.

But again, the number of barnacles in that image was quite small, and I wasn’t able to measure the individuals directly, so as evidence it left something to be desired.

What would really be useful, I thought, would be to retrieve other objects that had been floating out in the open ocean for a known amount of time to see what their barnacle populations looked like.

And that idea led me to the Global Drifter Program, as initially discussed in Season 2 episode 12, where I talked to Andy Sybrandy of Pacific Gyre, Inc., which makes the buoys that scientists drop in the water and then track using GPS data sent by satellite. Andy told me that the location of these satellites can be viewed on a publicly accessible web site, so what you could do is wait until one comes ashore and then ask a local to retrieve it.

And we tried to do just that in Episode 16, with only partial success. A drifter came ashore in Kenya and a local hotel owner was able to retrieve, but by the time he did someone else had already found it and scraped the barnacles off.

But I kept at it, with the help of volunteer Rochelle Reynolds. We had a lot of failures, a lot of near misses, but eventually we were able to retrieve a drifter in Hawaii and then two on the Pacific coast of Australia, but it seemed like these either grew significantly slower than barnacles in the western Indian Ocean or had had suffered significant predation.

So after many months of work I’d become convinced that the methodology would work, but I hadn’t yet managed to collect a single one in the western Indian Ocean.

I knew it was just a matter of patience, waiting for our luck to turn, and finally it did. On June 6 Rochelle and I noticed that a drifter was heading right for the island of Zanzibar, and it seemed there was a good chance it might come ashore.

Lo and behold, on June 10 it came right up to a small island off the coast of Zanzibar called Chumbe. This is a private island and preserve that tourists can visit and it also has its own staff scientists. So I reached out to them and they seemed quite interested to help. But there was something strange about this buoy. It kept bobbing up and down drifting north and south of the island with the tide. Now something to bear in mind is that by the time the location data gets to the public website, it’s four hours old, and it can be really tricky to figure out where something is now when all you know is where it was four hours ago. Long story short, the buoy eventually left Chumbe and started to head north. And I figured we’d missed our chance yet again.

But then we got our big lucky break. The buoy just stopped off shore, a few miles from the main town of Zanzibar. I’d never seen anything like this before. So I looked at Google Maps and I found a paddleboard tour operator called 2 Winds that was located just onshore of where the buoy was stuck. It turned out that this is an operation run by two expats, Josh and Arsheen, a married couple who had been doing development work on the island for years and then started a paddleboard company to help financial support their NGO project, which helps poor kids get ready for independent adult life. They’re really amazing people.

And it turned out that this was really a million dollar haul, because the buoy and the sea anchor attached to it were absolutely covered with hundreds and hundreds of barnacles, as you can see.

I’m extremely grateful to Josh and Arsheen for their help. If you’re ever in the amazing and historic cultural melting pot of Zanzibar make sure to go stand-up paddleboarding with 2 Winds, it looks like a blast.

Now, in one regard, this drifter buoy is a lot like the flaperon, in that there doesn’t appear to have been significant predation or mortality of the barnacles. Unlike the Australia drifters, it seems like every nook and cranny that Lepas like to live in has been settled. You don’t see the blotches that are left behind when Lepas die. So in both cases you have populations that should be a good reflection of how long these objects have been in the water.

The striking difference, of course, is that the Zanzibar barnacles are significantly larger than the flaperon ones. There are so many hundreds of them that it’s going to take a little while to do a full measurement and analysis, but I asked Josh to take pictures of some of the bigger one and what they suggest is pretty striking. The biggest one is 46 mm, versus 36 mm for the flaperon. And while the flaperon had a lot of barnacles between 20 and 30 mm, the drifter has a lot between 30 mm and 40 mm. And we know that the Zanzibar drifter was in the water for 10 months.

So that seems broadly consistent with the picture we’d gotten from the Stelfox mooring data.

This is really exciting data. This is the first time that anyone’s collected a complete and robust data set of Lepas barnacles that have grown in the open ocean in the western part of the Indian Ocean.

In my estimation, it seriously undermines the idea that the flaperon went into the ocean in March of 2014. It supports the idea that I've raised before, which is that the flaperon probably went in the water about a year after that.

I’ve reached out to two scientists who’ve been studying Lepas growth as a way to understand how things drift in the ocean and I’m hoping that we can publish this in a peer reviewed scientific journal.

There is one sour note I need to drop here — the Global Drifter Project is part of an office of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration called the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, headquartered in Miami. And the new budget that just got passed by a Republican congress and signed into law by Donald Trump will eliminate this office. So in the future in might no longer be possible to collect Lepas data in this way. This is just one small example of how America’s leadership in the world scientic community is being gutted, absolutely destroyed, just so that the rich don’t have to pay as much in taxes.

All right, so that we don’t end on a bummer, I want to share with you one more really interesting thing that I learned from Josh and Arsheen.

As you know, one of the other major mysteries about the flaperon is how it could be that there are Lepas growing all over its surface. Both Australian and French researchers found that the flaperon floated with the aft end sticking well out of the water. So come that part of it was covered with lots of Lepas? Is it possible that Lepas can grow out of the water? I launched a Kickstarter to raise money to buy a flaperon and put it in the ocean to see how Lepas would grow on it, but I didn’t come close to raising enough money, so unless some rich benefactor comes forward we’ll never know.

However, as it happens, Josh and Arsheen sent me a piece of evidence that sheds some light on the question. Zanzibar lies at the end of a pretty strong and consistent east-west current that flows over the north end of Madagascar and dumps stuff onto the shores of Tanzania. So they see way more debris from the deep ocean than practically anyplace in the world, and as a result they get a lot of Lepas coming ashore.

They send me this picture of a can that had quite a nice poplulation of Lepas on it.

Thinking about the flaperon mystery, I asked them to put it in the water and show me how it floats. They sent me a video that you can see at the end of the YouTube video posted above—in short, you can tell that the Lepas do a great job of really going right up to the waterline and not a millimeter more.

It’s just another further bit of evidence lending support to the idea that something is very wrong with how the flaperon floated. It’s a puzzle that I’ll continue to work, and we’ll see if we can’t find another more economical way to solve it.

After all, MH370 is a big mystery, and a lot of money has been spent fruitlessly trying to find it on the seabed. But I think that something that’s more valuable than money is determination, a willingness to think outside the box, and to work together to find crack problems that professionals can’t.

We’ll get there. It may take some time, but we’ll get there.

Why do most Americans and westerners believe the media saying that MH370 crashed in the South Indian Ocean, why are you so easily fooled by the government, Is it because of your low IQ or maybe you have prayed very little so God does not guide you to follow your right path?

Why do we keep studying the theory about MH370 crashing in the South Indian Ocean for 11 years without finding anything :( I know it crashed in the East Sea of Vietnam. "The plane just crashed, a few hours later there was debris floating in the sea and a yellow oil trail of MH370, we are Vietnamese people, we know, we are not ignorant. We tell the truth. All videos related to MH370 crashing in the South Indian Ocean are false. Be smart, be smart, be smart, don't let the Malaysian government and the US government,... deceive the people anymore.