MH370 Search Takes a Break [S2Ep29 video]

After less than a week of searching, Armada 78 06 heads to port

Today is Saturday March 1, 2025 and yesterday the Ocean Infinity ship carrying out the seabed search for MH370 left the search area and began sailing to the port of Fremantle, Australia, less than a week after it started the scan. In today’s episode we explain the rationale for the part of the search that’s just been completed, and discuss whether Ocean Infinity will likely return to the search area—and if so, when.

Last week we talked about how Armada 78 06 had launched three autonomous underwater vehicles of AUVs in an area of the seabed that had already been searched twice, once by Phoenix International during the initial search that ran from 2014 to 2017, and then again by Ocean Infinity in 2018. In both cases, obviously, to no avail.

Why look again? The short answer is that after a decade of analyzing and re-analyzing the evidence, investigators reached the conclusion that if all the Inmarsat data and all the other evidence means what they think it does, then the plane has to be in a fairly small area close to where the plane sent its last transmission at 0:19 universal time on March 8, 2014.

Now, for a more detailed explanation of why the plane has to be near there, check out Episode 11 of Season One, but for present purposes suffice to say that at that the moment it sent that transmission the plane had already run out of fueland so had already lost energy and altitude, then whoever was at the controls of the plane pushed the nose down into a very steep, almost vertical, nose dive.

Under such conditions it would have to hit the water in about a minute, as we discussed in Episode 4 of Season 2.

So obviously it’s not going to have gotten miles and miles away from the place where it sent that final transmission.

Now remember that this Inmarsat data doesn’t tell us excactly the spot where it sent that transmission, but it tells us how far the plane was from the satellite, and the sum of all possible locations makes an arc, and so what we’re looking at is the final or 7th arc (the outermost purple one in the picture below).

The plane must be near the seventh arc.

But when they did those two seabed searches, they didn’t find the planes wreckage. Why?

An idea that’s been kicked around for a while is that maybe the last time they searched the area were the plane wreckage was, but they just didn’t see it because the pieces were hidden behind a rock or down in a gully.

In fact, Australian officials took this idea seriously:

From 2-4 November 2016, experts in data processing, satellite communications, accident investigation, aircraft performance, flight operations, sonar data, acoustic data and oceanography gathered in Canberra to reassess and validate existing evidence and to identify any new analysis that may assist in identifying the location of the missing aircraft. They agreed that the methodology and effectiveness of the underwater search meant that if an area had been searched there was little to no chance that any aircraft debris had been missed.

“Little to no chance” — so, maybe there’s hope?

Well, not really.

In 2022 Australia revisited the issue, someone in the government got excited about Richard Godfrey’s ridiculous WSPR claims, so they decided to revisit the seabed data near the area he was proposing, and they produced a report that really shows the issue quite clearly.

There were really two issues, actually. The first issue was that the imagery of the seabed certain objects of unknown provenance sitting on the seabed. According to the report, “Geoscience Australia identified eleven contacts… Eight were identified as most likely geological in nature and three as possibly anthropogenic in nature.”

What if one of these anthropogenic objects was a piece of the plane?

The Australians sought the advice of a man named Andrew Sherrell, who explained why he didn’t think that any such isolated object could be from MH370. Victor Iannello talked to him and wrote about the conversation on his website:

Andy Sherrell is an experienced ocean engineer who has conducted deep water search and salvage operations for a number of missions. He was a key member of the team that reviewed the sonar data for the subsea searches for MH370 that were conducted by the ATSB and Ocean Infinity. Andy was also part of team that identified the debris field for AF447 off the coast of Brazil as well as part of the team that found Argentina’s ARA San Juan submarine. Andy graciously offered these comments as to why many of the MH370 promising contacts were never investigated further:

“Typically, if there were small isolated objects that appeared to be man-made and marked as a target, but nothing else was of interest within several kilometers then we did not investigate further.

We certainly took into account if the debris field did not look like AF447 or any others, however there still needed to be enough debris to be at least a fair amount of the aircraft to warrant further investigation.

Sure a small part of the plane could have drifted and sunk, but we were looking for the main field. A decision was made to focus on finding the main field of debris, not just one small piece – and likely all of those “potentially man made” contacts are from passing vessels given there was no associated debris within several kms.

Having said that, there is always a chance it [a tagged contact] could be from MH370, but based on our assessment the time it took to investigate each of these small contacts was not worth taking vs searching new areas.”

OK, that’s the issue of isolated piece of ambiguous identity. The other issue is what if there was a gap in the imagery and the plane is in that gap. In that 2022 report Geoscience Australia looked at those data gaps with a chart that looks like this:

You can see there are various kinds of data gaps, or what they call data holidays. There are places where either the swaths didn’t line up, or the equipment malfunctioned, they look like this. There’s a long thin purple line, and then little bleeps and bloops in purple. It would have been really unuckly for the wreckage to have aligned itself right inside those gaps.

Then you have areas like on the slope of that little underwater hill, where the sonar data is perfectly good, but you’ve got the problem of the shadows and crevices and boulders that make it harder to interpret what you’re seeing or are maybe hiding the wreckage in shadows.

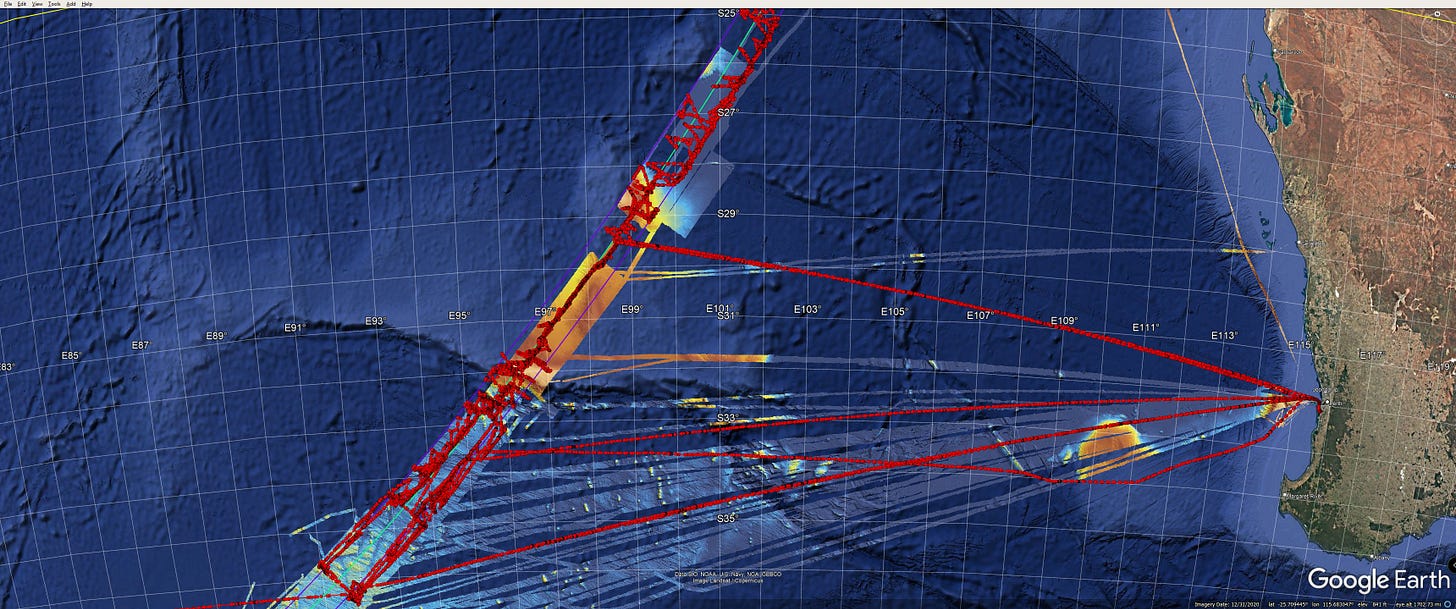

But as you can see these areas are quite small. The chances of the plane being there are already tiny. But just to make absolutely sure, Armada 78 06 has been using its AUVs to take a closer look at all these potentially problematic areas. If we look at how it’s been sailing over the last week, it’s been zigging and zagging in ways that look pretty random. But when you compare the path with the previously recorded seabed data, it seems like Armada 78 06 is deploying these AUVS mostly along steep-ish slopes and underwater ridgelines where the terrain is roughest, and where there would be the greatest hope that the wreckage might lie hidden.

A related question is that, now that the ship is heading for port, do we think it’s going to come back? If you compare the planned search area to the vessel tracks, it seems like they might well have pretty much covered most or all of the seabed region that was already scanned. So maybe they’re done with that part of it. And maybe they’ve decided that that’s the only part worth searching.

After all, they spent 9 days traveling from Mauritisu to get to the search area, they only search for five days, now they’re sailing to Fremantle which takes four or four and a half days, doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense to come all this way and search for such a short amount of time.

Well, a friend of the podcast David Byers reached out to Kevin Rupp, whose been collecting all this data and posting it online, and asked him whether it had been the plan all along to search for such a short amount of time.

Rupp answered: “Yes, union contracts usually stipulate crew changes every four weeks. Sometimes, this is waived, but [it’s] almost always four weeks. That’s what Seabed Constructor did in 2018.”

Rupp passed along this image showing Ocean Constructor’s path during the 2018 search, and you can see that indeed about every month or so it went back to Perth.

Now, Perth is a lot closer to the search area than Mauritius, so if Armada 78 06 does wind up carrying out an extended search, it will be able to stay on station a lot longer that it did during this first phase even if it does have to go back to port at the end of every month.

The ship is due to arrive in Fremantle on March 5, it will probably turn around pretty quickly with whatever supplies and equipment and new crew, and head back out to the search area. I’m planning to have more about that in the next installment, as well as more of an explanation of the search beyond the previously scanned area, and what the logic behind that is.

Jeff, note that if the "data holiday" is large enough to fit the debris field than the probability of finding the plane is high, not low.

Only if data holidays are smaller than the size of reasonable debris field they can be dismissed as potentia plane'sl resting place.