As the southern spring of 2014 approached the search authorities prepared to undertake a search of the seabed where their calculations indicated the plane had gone.

They hired a Dutch marine survey company called Fugro, which dispatched three ships to the area: Fugro Discovery, Fugro Equator and Fugro Supporter.

The area they were going to search had been defined by the probability density function we’ve described earlier. It stretched about 600 miles long and covered water that was about three miles deep.

The logistical and technical challenges of searching this 23,000-square-mile area were enormous. Because it lay so far from land, crews would have to stay out for a month at a time, in a clime that mariners considered to be among the most inhospitable in the world. Here in the fabled “roaring forties” the waves at times reach 50 feet high.

When the weather was amenable, the ships would reel out torpedo-shaped devices called towfish on six-mile-long tethers. Scooting along 500 feet above the seabed, these emitted beams of high-frequency sound. The echoes they received were descrambled by computer to produce photograph-like images of what lay below.

When the undersea terrain was too rugged, searchers deployed autonomous underwater vehicles, or AUVs, that darted more nimbly around obstructions.

In late October, the search vessel Fugro Discovery made its first pass towing side-scan sonar gear. Over the next few months it steamed up and down parallel to the 7th arc, imaging the seabed in lawnmower strips, gradually working outward from the center of the search zone.

In January of 2015 it was joined by Fugro Equator and Fugro Supporter.

By now officials were confident that they’d got the numbers right, and believed that success would follow in short order. As lead Australian crash investigator Peter Foley told one reporter, “the 1988 Moët is chilling nicely.”

Yet by April of 2015 it was clear that the search was coming up empty, so the governments of Australia, Malaysia and China decided to double the search area.

Australians officials continued to voice confidence that the seabed search would ultimately prove successful. On the second anniversary of the disappearance, ATSB head Martin Dolan told the Guardian that MH370 would be located before the end of the year. “It’s as likely on the last day [of the search] as on the first that the aircraft would be there,” Dolan said. “We’ve covered nearly three-quarters of the search area, and since we haven’t found the aircraft in those areas, that increases the likelihood that it’s in the areas we haven’t looked at yet.”

Martin was mistaken. Basic statistics will tell you that the further the search vessels moved away from the 7th arc, the lower the probability that they would encounter the wreckage on each successive pass. In the analysis that the DSTG had published the previous fall, it had calculated that there was effectively a zero percent probability that the plane hit the 7th arc north of 34 degrees south longitude or south of 41 degrees south longitude. And the ships had already scanned that segment of the arc out to a distance of 40 nautical miles in either direction.

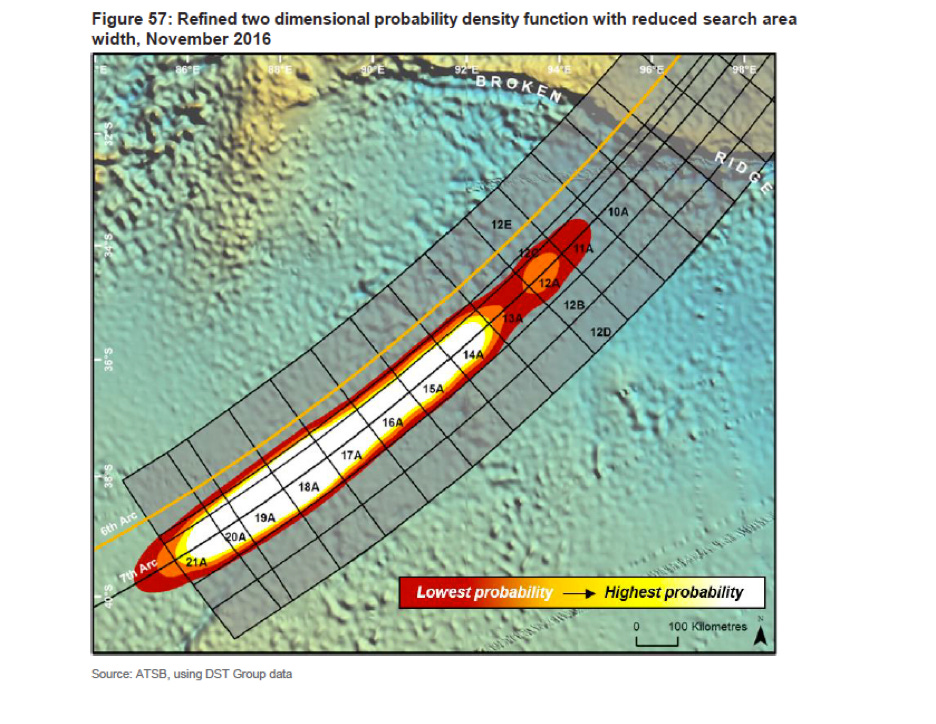

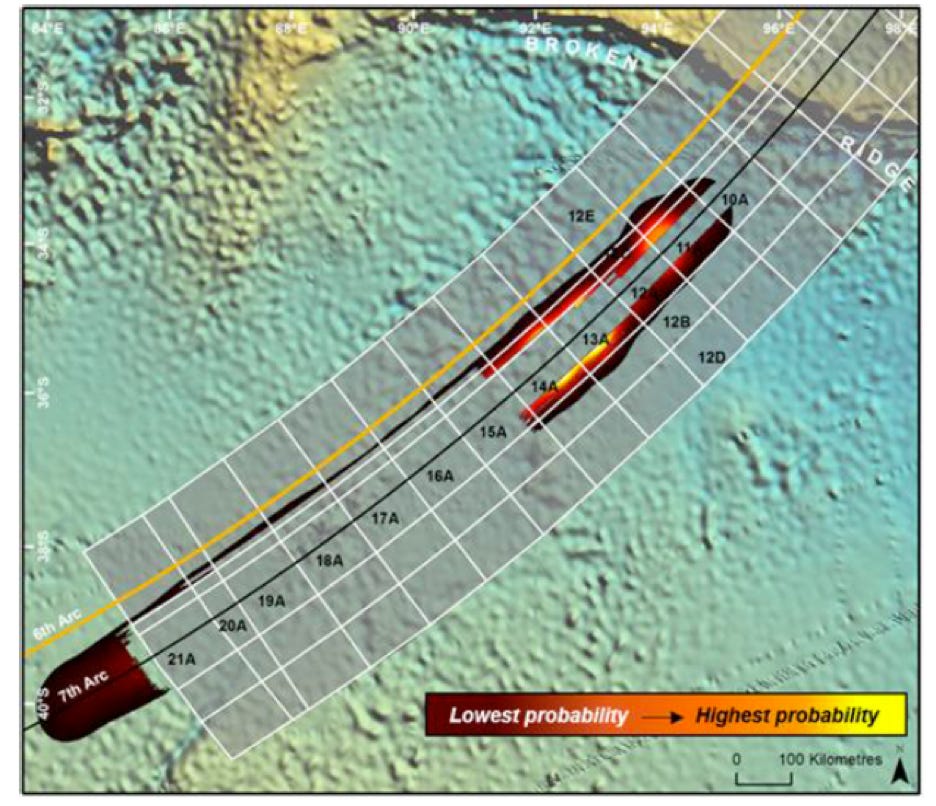

In November of 2016, with just a sliver of the 46,000-square-mile search area still unscanned, the ATSB convened a meeting of its experts to grapple with all the different ways they could have gone wrong. They decided that the only way to make sense of the data was to assume that the plane must have wound up north of the previously defined search. The experts defined a new area, 10,000 square miles in size, that straddled the 7th arc between 32.5 and 36 degrees south latitude. Given the signals received by Inmarsat, this was the only place the plane could possibly be. “Based on the analysis to date, completion of this area would exhaust all prospective areas for the presence of MH370,” they concldued.

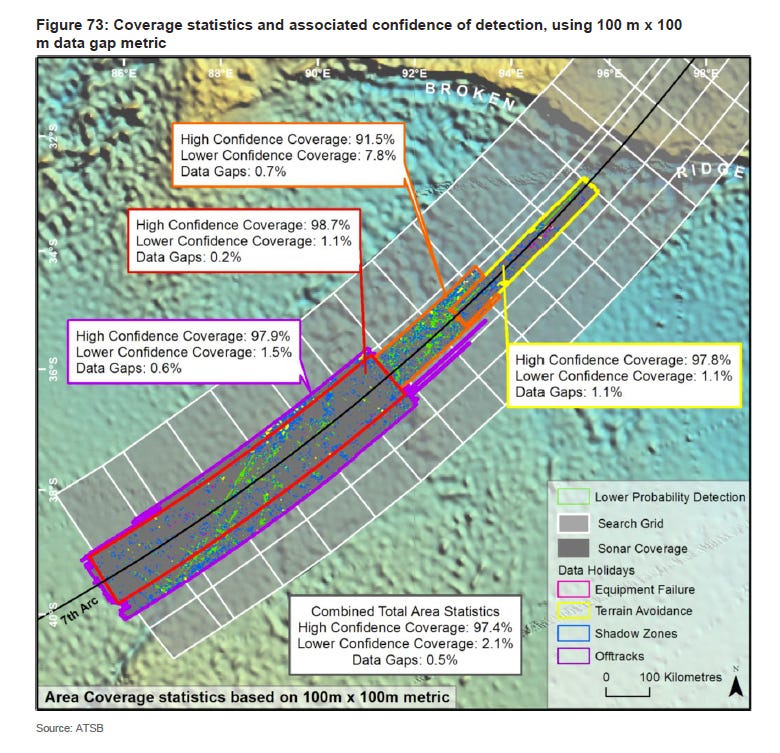

At the end of the day what they were left with was a chart of the seabed where they initially had been very confident they were going to find the plane, and at the end of which they were pretty sure it wasn’t.

Here’s a map of the probability heat map once they excluded the part they’d already searched:

Here’s a map of how confident they were that they could rule out the planes location, i.e., that it hadn’t fallen into a crevasse or be hiding in the shadow of a cliff:

For me the question everyone should be pondering was: Did these results cast doubt on the soundness of the Australians’ approach?

To watch Deep Dive: MH370 on YouTube, click the image above. To listen to the audio version on Apple Music, Spotify, or Amazon Music, click here.

1. Can you get the Inmersat data from MH17 which was shot down over Ukraine, and cross reference the known location of MH17 with the Inmersat data to see how accurate it is? Can any discrepancy be applied to MH370 data?

2. What military assets were in the South China Sea near to MH370 last known location? Warships etc? They'd definitely have been monitoring air traffic.

3. I believe Inmersat is used for onboard phone calls from passengers. We're any calls made by passangers on that flight, when was last call made? Was there any calls in progress when it disappeared, or in the times after it's last known contact?