The Blind Spot [S2Ep36 video]

Considering the inconceivable in the search for the missing plane

The second phase of the third seabed search is over, Armada 78 06 has moved on to its next project, we have a couple of months at least until any further progress is made, so I want to review where we are.

A quarter million square kilometers has now been searched, including about 10,000 in 2025. This is not any old stretch of ocean, this is the area containing the vast majority of the search probability calculated by Australia’s top scientists. This where they calculated the plane would be.

And so far, it isn’t.

There are two possibilities, two competing hypotheses. Either the Inmarsat data is good, in which case it’s overhelmingly likely that the plane went south but just hasn’t been found.

Or, the Inmarsat data isn’t good, it’s been tampered with, in which case the reason the plane hasn’t been found is that it isn’t there.

Now, it’s really important to understand that the more of the seabed that gets searched without finding it, the more of the probability zone gets excluded, the less likely hypothesis 1 becomes, and the more likely hypothesis 2 becomes.

So this is why at this point I believe that the prediction of hypthosis 2, which I pointed out in 2015, is overwhelmingly more likely at this point, and will only become more so.

The failure of the seabed search means that the plane did not go south.

Unless.

There is an escape hatch to his logic. Under the principle of Cromwell’s Rule, an aspect of Bayesian inference which I discussed in Episode 21, amassing more evidence that undercuts a theory does not change its probability if there is 0 percent chance that it is wrong.

And this in a nut shell is why so many of the people who’ve been following MH370 and theorizing about the case refuse to accept that the plane might not be on the southern seabed. Because they assign a zero percent chance to its being possible.

It is simple inconceivable to them. It’s a blind spot. An aspect of the case that they are unable to see.

So in today’s episode I want to explore why they have decided that it is inconceivable, and why I think their sense of certainty rests on shaky foundation.

I’ve often talked about how, by June 2014, a solid consensus had formed around the idea that the Inmarsat data meant that the plane must have gone south into the southern Indian Ocean, but I had begun to realize that there was an alternative explanation for that data, namely that someone could have snuck through the unlocked hatch to the E/E bay and fed spoofed data into the SDU’s Doppler precompensation system.

In other words, the plane could have been cyberhijacked.

At the time I was the member of a group of online individuals who had taken to calling themselves the Independent Group. Many of these people had impressive technical credentials, and were instrumental in explaining to the general public what the Inmarsat data was and what it meant for the fate of the plane, none more so than a Colorado satellite communications engineer named Mike Exner. I’ve talked before about some of the personalities involved in the public effort to solve the mystery of MH370, I would put Mike in the same category as Victor Iannello in terms of someone who actually knows what he’s talking about, techically speaking.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that without Mike Exner, I don’t know if any of us would have really managed to understand what the Inmarsat data was all about. And why, if read as written, it unambiguously means that the plane went south.

But here’s the thing. Mike is completely unable to accept even a .001 percent chance that the Inmarsat data could have been tampered with. And I think more than anyone else on the planet he has used his influence to ensure that that possibility is regarded as, frankly, a conspiracy theory. A silly nonsense. Perhaps the venue in which he exerted this influence most powerfully was the Netflix documentary “MH370: The Plane that Disappeared.” If you’ve seen it you’ll recall that in episode 1 I explain how Captain Zaharie might have hijacked the plane, then in Episode 2 I explain how Russian hijackers could have hijacked the plane and spoofed the data. I think the fillmmakers did a really good job of allowing me to explain the basic principles of the idea.

But then they pretty much blow the theory clean out of the water by showing Mike Exner saying this:

I’m intimately familiar with how that satellite system works, as are a number of my colleagues, and we’re absolutely certain that the plane turned south and not north. It was surprising that Jeff decided to take off on this route. Jeff’s work, in my opinion, is simply a fiction that he has woven and convinced himself is feasible. But it’s all based on fantasies. It’s not based on reality.

In the context of the show, it’s utterly unambiguous that Mike is right. Anyone who’s watching at home is going to understand that the idea of a third-party attack is just silly. Mike just has that weight of authority.

But of course, out of the context of the documentary, I think it’s urgent to ask, if we’re at all serious about solving this mystery: why is he so sure that there’s a zero percent probability?

How does he know that?

Well the simplest thing to do is to ask Mike, so I sent him a DM on Twitter, he responded:

There is zero evidence 370 was the subject of a cyber attack. OTOH, there are multiple lines of solid evidence Z hijacked his own plane and flew it to the SIO. You know this as well as I do. So why keep playing this game?

Of course, I strongly disagree that there’s zero evidence that it was cyber attacked, as I’ve laid out in detail in two seasons of this podcast.

What’s germane is that Mike does not think I’m right, and he’s never been willing to entertain the possibility, all the way back to 2014, when I was kicked out of the Independent Group for publicly raising the possibility of a hack.

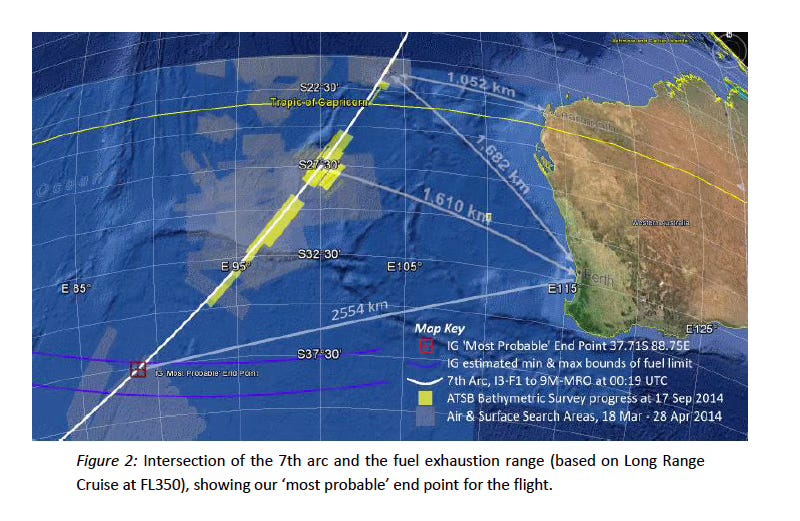

Specifically, in late 2014 the Independent Group, of which I was a member, published a white paper in which they calculated an endpoint for MH370, in hopes that the Australian and Malaysia governments would go look there. I was a co-signer of this paper.

The paper said that the plane had flown to “37.71S 88.75E … uncertain by perhaps 100 NM along the arc” and within 20 nautical miles of the seventh arc.

Their search area looked like this.

Then a few months later I observed that a hack was possible and if one had been carried out, the plane would not be found in that area.

I was kicked out for raising that doubt.

Now, what’s extremely germane to understand, is that I was right, and they were wrong. The plane was not found in their search area.

Of course, they revised their search area, and that area was searched without success, and in fact time and time again any area that’s been proposed has been searched without success. Every analysis of the Zaharie suicide flight scenario that’s been tested has been wrong.

As I said up top, the evidence keeps piliing up against hypothesis 1, and in favor of hypothesis 2, and yet all of the people who accept the conventional wisdom are not willing to admit the slightest glimmer of self doubt.

They will not investigate the issue, they will simply declare that it is too ridiculous to discuss.

So why? Why are they so stuck in the mud?

There really two main objections to a cyber attack scenario. Any potential hijacker has two very technically difficult challenges to overcome if they want to steal the plane and take it north. One is that they have to alter the BFO data to leave a false trail of breadcrumbs. The second is that they have to fly the plane from the electronics bay.

If either of these two things is impossible, then it its not possible that the plane was hijacked by someone other than its own flight crew and flown to the north instead of to the south.

But the standard is high. To show that this idea is 0.00000 percent possible, you can’t just explain how difficult it would be, how smart a person would have to be, how elaborate their equipment would have to be. You have to demonstrate that it is physically impossible.

And let me say, that there are a lot of situations in which both of these things would be quite clearly impossible. It would not be possible on a 757, because that is not a fly by wire plane. It would not be possible on any Airbus aircraft, because the electronics bay is not accessible from the passenger cabin. And so on. In fact, for the vast majority of planes flying in 2014, and pretty much all today, the vulnerability that I’m proposing did not exist. The idea really is 100 percent impossible.

But. Not. For. MH370.

It is different. There are no physical or electronic obstacles that I’m aware of, that anyone has ever pointed out to me, that makes either of these things impossible.

Let’s start with altering the BFO data. I came up with this idea, but Victor Iannello really elaborated it quite a bit, as I described in Episode 10 of Season 1.

The idea is that the box that creates the BFO value, the Satellite Data Unit, calculates it from navigational data that it obtains from another box in the electronics bay, and if you jack in and feed it falsified location information, or if you patch into the SDU and change an internal parameter, the plane will send signals that leave the false impression that it has flown into the southern Indian Ocean. And this allows the perpetrators to get away scot free.

Why is this impossible?

In the Netflix documentary, Mark Dickinson of Inmarsat has this to say:

The idea that someone predicts that we would analyze the data in this way, when we’d never done it in the past before, doesn’t seem particularly credible at all.

This has been Inmarsat’s position since 2014, when I interviewed them along with Miles O’Brien for a Nova documentary. They can’t imagine how someone else could be so smart as to have figured out this attack vector before they did.

That is a very dangerous mentality to have in a contested security environment — to assume that your attacker can’t possibly be more clever than you.

And it’s very much worth noting that Dickinson is not saying that there is any physical reason why the spoof couldn’t be carried out. In my reading, he’s tacitly acknowledging that it could be.

OK, let’s move on to part two. Can you fly a 777 from the electronics bay?

Mike Exner says no.

I wanted to understand why, so I DM’d him on Twitter, he expressed his skepticism this way:

Do you have specific information that a 777 can be controlled from the E/E Bay? The absence of any documentation supporting that theory should answer the question.

I wrote back to him:

So, to make sure I understand correctly, you consider a system safe against cyberattack so long as there is no documented evidence that a vulnerability exists.

To be clear, I was being sarcastic. If you are in a security mindset you do not assume that you are safe because you don’t know if a system is secure or not. You have to assume that you are vulnerable.

It’s like if you’ve got a house in a bad neighborhood, you can’t just assume your doors and windows are locked because you haven’t heard otherwise. You have to check every door and window

Another skeptic is Mohd Fuad Sharuji, who served as Crisis Director for MH370 and MH17 in the wake of those incidents, put it during the Netflix documentary:

Anyone who gets into the hatch can disable the transponder and disable the communication systems. But it is impossible to fly the aircraft from the avionics compartment. It is impossible.

I reached out to him to ask him how he could be so certain. I wrote to him on LinkedIn, and he answered:

It is simply impossible to control the aircraft flight and engine controls from anywhere else other than the cockpit. Whilst there are flight and engine control computers in the avionics compartment, there is no equipment to provide inputs into these computers like throttle, control columns, rudder controls, flaps, etc… The computers receive these inputs directly from the cockpit via sensors in the inputs.

Secondly, there is no provision on this particular aircraft (9M-MRO) that was designed to be controlled remotely.

Hence my conclusion that this is just impossible to control the aircraft from the avionics compartment.

I was very grateful to Fuad for responding to me. I still had questions, though.

I wrote back:

You are of course entirely correct that there are no control inputs in the electronics bay, so if one were to enter it empty-handed it would be entirely impossible to control the plane from there. And I agree that it would be impossible to control the plane remotely.

However, I wonder if you've considered whether the flight control system might be vulnerable to a sophisticated attacker who was equipped with the gear necessary to patch into the ARINC 629 bus. I've been speaking with a number of leading cybersecurity experts as part of my reporting, and it appears that the ARINC 629 was not built with any kind of security layer. It's hard to know for sure without conducting a full penetration test, ideally with the cooperation of Boeing and leading suppliers, but it seems that it might be possible at least in principle to spoof control-system signals to take command of flight-surface actuators.

He replied:

Firstly I have to admit that I’m not an expert on the aircraft navigation system. However, with my aviation knowledge as an aircraft engineer and in flight operations, I still very much doubt your theory. Whilst it may be possible to hack the ARINC 629 computer and processing unit, the net effect of this would send spurious fault warnings to the cockpit. However, this would not result in the aircraft maneouvering into a new flight path as this would require physical pilot’s input which can only be done from the cockpit. The autopilot would automatically disengage which will require pilot’s direct control of the aircraft.

Even then I don’t see how it is possible to hack the system remotely as there is no electronic or mechanical means of doing so remotely. The system is very much tamper-proof.

Again, I was grateful to Fuad for responding, and remain grateful for responding, but frankly I find his answer unsatisfying.

Long-time viewers of this podcast will know that I have talked to a number of cybersecurity experts, and not one of them has told me that hacking into the flight control system from the electronics bay is impossible.

And to be frank, I believe that Fuad honestly believes that you cannot do this, but he is not a cybersecurity expert.

At one time in his career he worked in aircraft maintainence but after obtaining an MBA his career has been in crisis management, which is a branch of corporate communications. He is not a cyber security expert and he has not studied aircraft control systems of vulnerabilties. As he himself puts it, “I’m not an expert on the aircraft navigation system, but I still very much doubt your theory.”

So while his position is that he very much doubts my theory, but when he goes in front of the camera he says that it is impossible. Which, in the context of the show, is a clear signal to the viewer that the plane could not possibly have been hijacked in this way.

But again, there is every difference in the world between 99.99 percent impossible and 100 percent impossible.

And what I’m hearing again and again is that there are a number of people who all have strong gut feelings that they can’t imagine a cyber hacker taking control of a 777, and they’ve all collectively convinced themselves that there’s a zero percent chance that they’re wrong, so they don’t even have to look closely at the issue, they can rest comfortably in their sense of certitude.

And every time they suggest a search area, and say that the plane must be there and it’s not, they don’t have to revisit their sense of certainty because there’s a zero percent chance that such wise and studious people could be wrong.

OK, is there anything that could shake these people out of their complacency? Is there any development in the world that could cause them to wonder if maybe the world doesn’t work the way they think it does?

Up at the top I mentioned that I have a new article out in Vanity Fair. It’s called “Flight Risk,” and it’s about cybersecurity in aviation.

This is an article that really started for me with MH370, and the possibility of cyber attack. Because if MH370 really was taken by sophisticated third-party attackers, that fact would have a number of consequences. It would predict certain things.

For instance, it would predict that a sophisticated and malicious entity, what is known in the trade as a persistent threat actor, is out there in the world doing harm.

And lo and behold, that prediction was born out. In the wake of MH370, Russia has been waging a wideranging campaign of sabotage, assassination and cyber hacks against the democratic west, what we call hybrid warfare. In recent years these attacks have targed civil aviation in the form of GPS spoofing and, more recently, the placing of incendiary devices in air cargo shipments.

Now I’ve talked about all of these things in the course of the podcast.

As the years have gone by, the picture has become clearer and clearer. Russia, who I pointed out in 2015 would be the culprit if MH370 was hijacked, has done more and more things that are consistent with that role.

They have shot down airliners, they have hijacked airliners, they have conducted wide-ranging spoofing attacks against airliners GPS systems, they have planted incendiary devices in air cargo.

As Ken McCallum, the director of Britain’s domestic intelligence service, said recently in a rare public speech, Russian military intelligence “is on a sustained mission to generate mayhem on British and European streets.” He added: “We’ve seen arson, sabotage and more. Dangerous actions conducted with increasing recklessness.”

And yet the aviation community has been slow to wake up to the threat of cyber attack, and particular to its acute vulnerability to cyber attack from Russia.

And within the MH370 community there remains a steadfast resistance to the possibility of cyberattack, despite everything that’s happened. And I think a big part of that is that there are a lot of very influential people who would feel their status of experts undermined if they were to admit that they were wrong about such a substantial aspect of the case.

In other words I think it’s about ego.

But I would once again beg, plead, urge, prostrate myself, to everyone involved in the case, to please reconsider. Let bygones be bygones. This case is too important to get hung up on personal emotions.

The more the seabed search fails, the more urgent it is to consider what the alternatives are. The only thing we have to lose are our chains.

Jeff,

Purely by happenstance, I came across this last night:

https://youtu.be/kDz0ERQw57o?si=VyQIphAY-CBBl6f8

Though it's ostensibly an analysis of the "Monty Hall Paradox," often employed on the old game show, "Let's Make a Deal," it's really an explanation of Bayesian statistics, and how they cut against "human nature" leading to doubt, disagreement, and even hostility. Very much in keeping with your friends in the Independent Group.

There are some excellent questions and ideas in response to today's video. Looking forward to seeing your responses! The question that keeps going through my mind concerns the navigational error shown in the BFO data, and how much that led to Inmarsat's determination of the plane flying south, or was it simply "noise" that the fancy mathematics had to erase in order to make a determination of the southerly route? And has the discrepancy between the BTO and BFO data in the likely crash site been satisfactorily explained?

Jeff, thanks for your persistence. Several questions. There are many holes in this straw man but I think we need to put together some type of realistic scenario.

It would seem that it might look something like this.

One person enters ee bay prior to take off or during initial ascent and plugs into comms and autopilot.

new destination entered and engaged on autopilot at the same time of good night.

Cabin depressurized

Crew and cabin oxygen masks come out.

3 hijackers have oxygen supply from scuba hijacker.

2 hijackers enter cockpit.

Announcement made returning to KL for emergency.

New route sets to exit strait and come out to ocean.

Passenger oxygen depleted followed by crew.

New destination input to autopilot.

Heading north on 7th arc unaware of satellite.

Plane goes north and crashes or lands in Russia.

I would bet lands based on the response of hijackers daughter.

The intent could have been to keep passengers alive with little oxygen but when they all perished, everything needed to be hidden quickly.

China has no problem hiding the deaths and I’m sure got something in return from Russia.

As I’ve said motive is money Russians invested and lost in 1MDB.

As I’ve said before I lived in Shanghai in 2014 and traveled to KL on Malaysia Air on red eye. On these flights the lights are on for at least the first hour while the stewardesses hawk merch. Chinese are always active on their phones and frequently ignore staff direction. It’s hard to believe that pax wouldn’t be actively trying to use phone if they were awake. That’s why copilot got a ping.