Search Week 4: One Mystery Solved, Another Emerges

Dogged by towering waves, Armada 86 05 pulls the plug and heads for Fremantle

Phase 2 of the seabed search for MH370 has ended, as Ocean Infinity’s search ship pulls its robot subs from the water and heads for port. In today’s episode we’ll talk about what they accomplished in the fourth week of their seabed scan and what lies ahead for future searches. We’ll also solve a mystery that cropped up in last week’s episode and see what we can make of a new one — namely, what some entries in an Australian port schedule can tell us about Ocean Infinity’s plans.

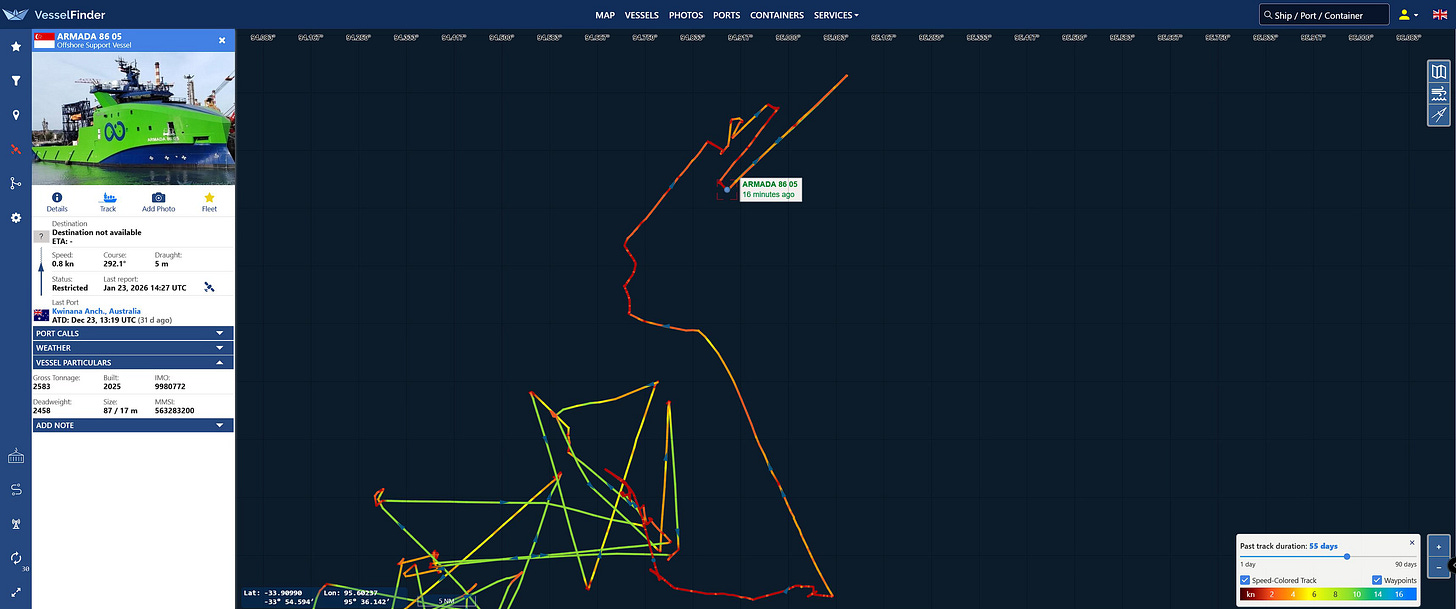

Last episode dropped January 20; at the time Armada 86 05 was moving slowly, apparently just trying to deal with the huge waves that were making it impossible to deploy any AUVs and hence to make any progress in continuing the search of the seabed.

In the days that followed, the weather remained rough, and this is the path that Armada 86 05 did.

As you can see, it was laying down a track colored red, which means that it was going slowly. It wasn’t following the usual movement pattern that it makes when deploying and retrieving AUVs, as we can see in this earlier part of the track (on the bottom, at left), where it’s moving fast and straight in green, then slowing and turning in the red sections in the corners (that’s where it’s retrieving and deploying), and then going straight and fast again to the next retrieval or deployment point.

It was kind of meandering around slowly in curves, and then it started to do some straight segments. That made some people speculate that, if it wasn’t doing its full normal deployment of AUVs, then maybe it was deploying one or two. As Kevin Rupp wrote on Twitter on January 23, “We’re thinking Armada 86 05 has had an AUV or two in the water since yesterday. The weather has improved, and currently the Wave Heights are under 3 meters.”

Well, if so, the operation didn’t last long, because later that same day Kevin wrote, “Armada 86 05 appears to be departing the search area and is headed to Fremantle.”

So that was it. The current phase of the seabed search appears to be over. Probably very little, if any, scanning took place since last week thanks to all that stormy weather, so for now the total for the whole 2025-to-2026 search effort remains at 7236.4 square kilometers, less than half of what they’ve said they plan to complete. Compared to the blistering pace they managed in 2018, this is very slow rate of progress indeed.

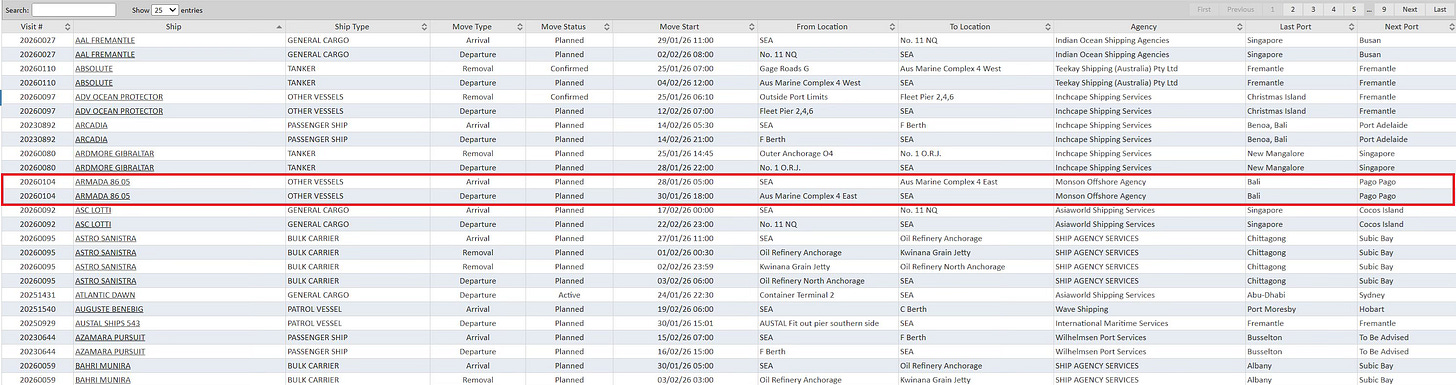

According to the Fremantle port registry, the ship is slated to arrive on January 28 at 5am and then depart on January 30 at 18:00 hours or 6pm. This is a longer stay than the ship had on its last visit there, so probably going to do more serious reprovisioning and get a change of crew.

Now, up top I mentioned that I would solve a mystery from last episode, so let’s get to that. I pointed out that viewer @glenn354023 had made an intriguing observation, namely that if you divide the area that the Malaysian government was reporting searched each day by the linear distance that the AUVs had traveled, it appeared that each AUV was scanning a strip that was 1.8 kilometers wide, or 900 meters on each side.

That seemed like further than the AUVs are supposed to be able to see, so I went to the website of Kongsburg, the company that makes the AUvs, and found the brochure for the HISAS 1030 sidescan sonar system that the AUVs use. It states that “Maximum range (each side of vehicle): 200 m @ 2 m/s and 260 m @ 1.5 m/s AUV speed.”

This just made the mystery deeper, because if the maximum range was 260 meters, then that implied that there was more than a kilometer of each search strip that wasn’t properly getting imaged. Worse case scenario, the AUV could go right past the airplane’s wreckage and not even see it.

I reached out to my usual sources for things like this, Kevin Rupp and Don Thompson, and they both said that they thought that the 1.8 km figure was correct, that the AUVs really can see out that far.

Don pointed out that there are two systems at play here, side scan sonar, or SSS, and sythetic aperture sonar, or SAS. Don said that synthetic aperture sonar can see objects in great detail, but in only works at relatively short distances, whereas SSS can see further, up to and beyond that 900 meter range, but at lower resolution.

Now, Kevin and Don are both smart guys, and in my experience they tend to get things right. But to be really sure I wanted to go to certified specialists in that particular technology.

So I reached out to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. These are the people who found the last airliner that went missing over the middle of a ocean, Air France 447, using REMUS AUVs equipped with side scan sonar technology.

They put me in touch with Captain J. Carl Hartsfield, the director and Senior Program Manager at the Oceanographic Systems Laboratory, and he agreed to answer my questions.

Naturally I asked him to join me on video but he wasn’t able to get permission from the media relations people on time so I had to settle for written answer via email.

I first asked him about his background. He wrote:

I am a retired U.S. Navy submarine Captain and Commodore that also, somewhat uniquely, specialized in rapid fielding of advanced technology for defense and industrial applications. At WHOI, I direct the Oceanographic Systems Lab (OSL) that designs, builds, and operates cutting edge unmanned REMUS vehicles that advance both science and defense work. OSL operates these deep-sea vehicles world-wide for science, defense, and industry – folding experience back into our designs.

So this was definitely my guy. I asked him about difference between sidescan and synthetic aperture sonar. He wrote:

Synthetic Aperture Sonar and traditional side scan sonar use the same basic first principles – you send active pings near horizontally in the water to get a pixel return of what the bottom looks like. Synthetic Aperture combines those pings over time to get multiple returns on the same target and build an even better picture. They do this by mathematically correcting each transmission for the geometric movement of the collection vehicle providing a very clear, multi-faceted picture of the target. Just like with an antenna, the bigger you build it, the more gain you have to image the target. SAS makes a bigger sound receiver by artificially stitching together the motion of the much smaller physical array that is pinging over time. All that tech talk boils down to this – you can build a big virtual sonar array that “sees with sound” much, much better if you can keep up with the geometric picture accurately over time and sum up the results with a lot of math. The cost for this extra clarity is significant – the autonomous vehicle must be very stable with accurate navigation, and the swatch coverage goes down significantly. This all translates into expense and complexity that is often only warranted if you need super clear resolution on smaller, discrete objects in one pass.

The physics of side scan requires you to balance how far you can see in each swath with the size of target you can detect. In other words, if you are looking for a ship, you can use much lower resolution with bigger swath coverage. If you are looking for something as small as a teacup, the resolution must be very high and the corresponding swath width low. …if your target is something large, like a plane engine in a debris field, you do not need a SAS because the wreckage will have many returns that tend to stand out on the deep-sea floor even at low resolution.

I then asked him about Woods Hole’s discovery of Air France 447’s wreckage.

The wreckage was discovered and mapped by three REMUS 6000 deep survey vehicles used from the deck of a single ship. Each had traditional 120 KHz side scan sonars with swath widths on the order of 700 meters on each pass. … The debris field was found at a depth of 3,900-meters in high geology relief portions of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Once found with sonar, the wreckage was optically imaged providing a photo mosaic road map used to identify the location of the recorder. Subsequent recovery of that device with a tethered ROV.

I want to thank Captain Hartsfield very much for taking the time to answer my questions, and I hope that I can have him on in person for a future episode of the podcast.

For point of reference, the depth that AF 447 was found at was nearly four kilometers, the area that Armada 86 05 has been scanning is roughly the same, so it’s roughly a similar degree of technical challenge.

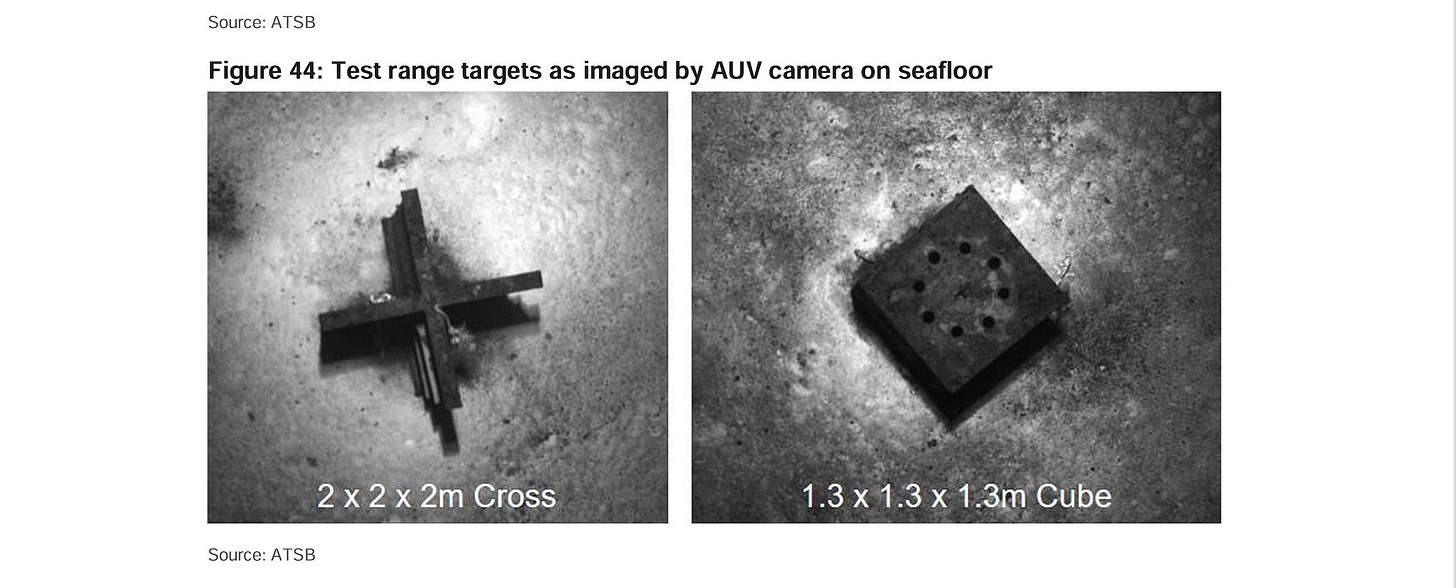

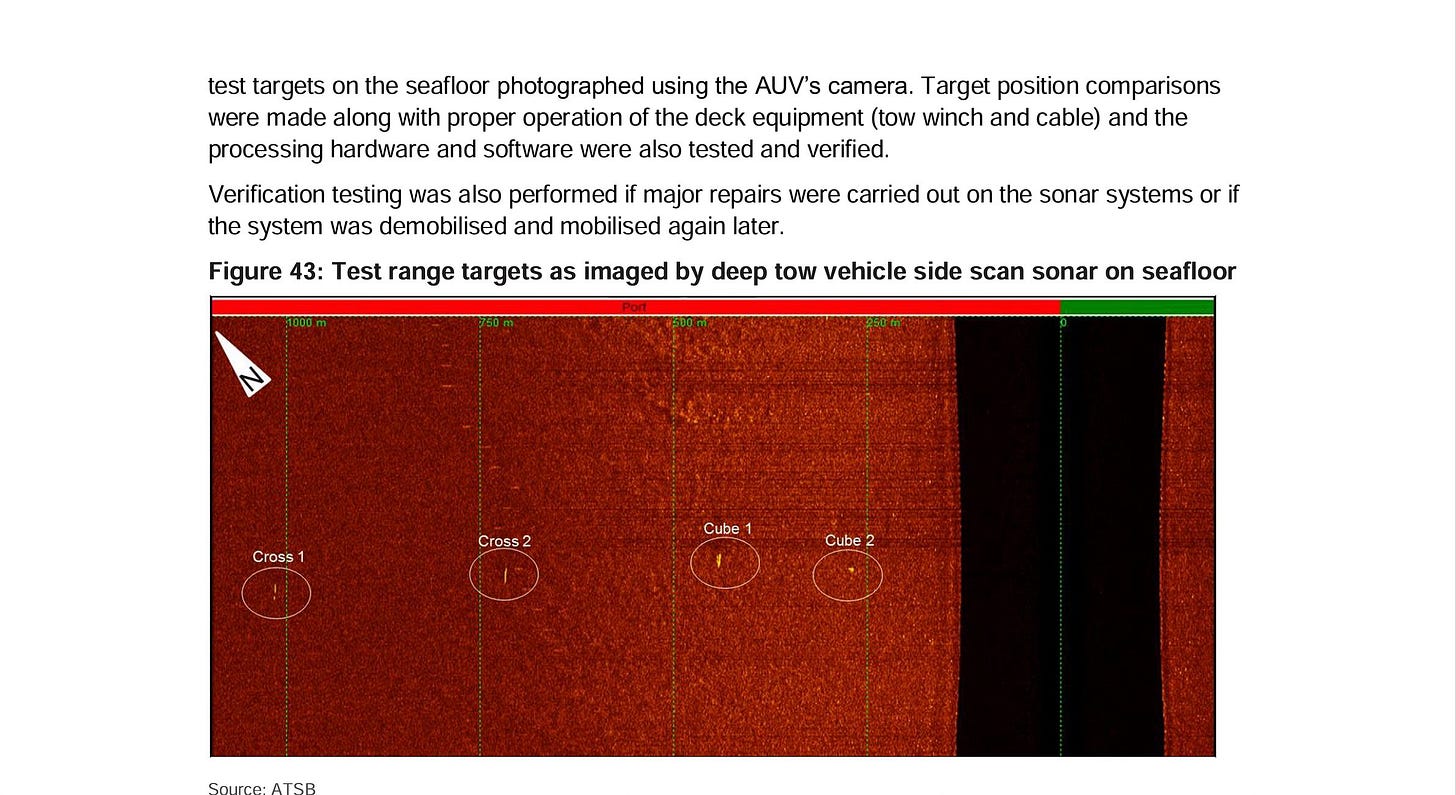

As I was discussing this with Kevin Rupp he referred me to the report that the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) published after their original seabed search, it details the tests that the investigators performed on objects that had deliberately been sunk off the coast of Perth to see the range at which they could be picked up by the sidescan sonar.

They were in the shape of a cube and a cross.

Here’s an image of a scanning run, as you can see the cross shape was visible at a greater than 1 km range.

Kevin went back to look at the ship tracks that the search vessel laid down during the seabed scan funded by the ATSB, he found that they ship tracks were 2 km apart, so even further than Ocean Infinity’s AUV scans.

I want to point out that that earlier search used a slightly different technology, the sonars were carrried on underwater sleds towed behind the ships, so the surface vessels traveled in straight lines, rather than following a zigzag pattern, picking up and and deploying AUVs, like Armada 86 05 has been doing. So it was much easier for those of us playing along at home to see exacty where they were scanning.

So this is the answer to that first mystery I mentioned: the reason that the scanning runs are so wide is that they’re using a lower-resolution version of sonar imaging that can see farther, they’re counting on the ability to pick up big fields of debris, and potentially large objects like engine cores and landing gear, that will alert them to the fact that something is there. Then if they spot something they’ll then go and take a closer look to confirm that it is indeed the aircraft.

All right, and let’s now wrap up by talking about the new mystery that’s emerged, namely: where will Armada 86 05 go next? Will it return to the search area after repositioning, or move on to a paying project somewhere else and leave us sitting on our hands once more?

The Fremantle port schedule shows that at the moment the field for “Next Port” is Pago Pago, in American Samoa. That sounds like bad news.

However, Twitter user Felix Toennessen replied to Kevin, “I took a look at some of your old screenshots in 2018. In March 2018 it said TO SEA and NEXT PORT Durban. However, Seabed Constructor still conducted two search phases after this Fremantle pit stop.”

I mean, it is definitely the case that these port entries are not a perfect predictor of what actually happens next. So while I wouldn’t take it as a given that the seabed search will continue, I wouldn’t give up hope just yet, either. Remember, last year it was in April when Ocean Infinity decided to give up for the season because winter weather was coming. So we still have a couple of months left for the search to go on. Fingers crossed…

Hey Jeff! Been following this case and your work on it since the night the plane went missing. Just wondering if you saw the podcast with the guy you just were just on with Sit Down With Sid, he had Blain Gibson on it 2 days ago. Curious on your thoughts on it? Thanks for all your dedication and work you have put into solving this mystery! -Shannon Sissel

technical note on SSS range and resolution:

https://www.hydro-international.com/content/article/insides-of-side-scan-sonar